A Summary Report of the 1st Middle East Advisory Board Meeting for Medication Management and Safety

Advancing Medication Safety: A Summary Report of the 1st Middle East Advisory Board Meeting for Medication Management and Safety. Dubai, February 2020

Dr Ulfat Usta: Chief Pharmacist at American University of Beirut Medical Centre, Beirut, Lebanon.

Rania Al-Jaber: Pharmacy Automation and Support Specialist, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Maher Mominah: Manager, Pharmacy Automation and Support Service, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Khalid Dayem: Senior Automation and Informatics Manager, Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Rabih Dabliz: Senior Manager, Quality & Medication Safety Services, Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Ahmad Chaker: Manager, Sterile Preparation Center, Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Sajjad Ahmad: Clinical Pharmacist & Pharmacy Informatics Lead, Al Ain Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

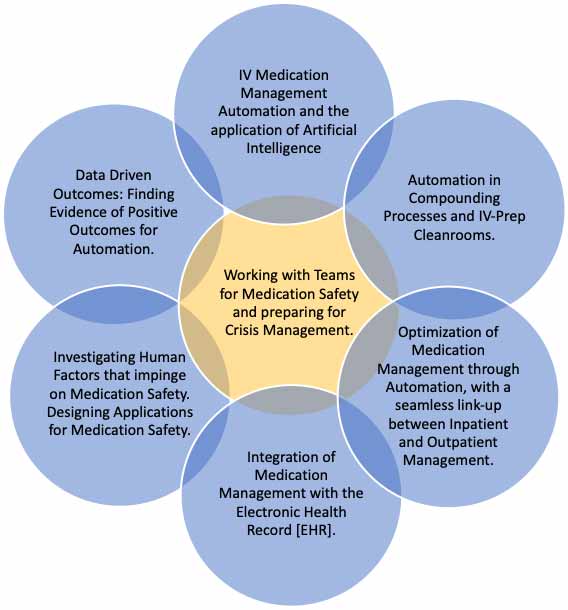

The Board for Medication Management and Safety set itself the following objectives during its first meeting:

- Review the region’s current medication management landscape, identify specific challenges, and propose solutions.

- Assess the impact of tools that may add transparency, and safety to the medication chain.

- Discuss opportunities to create a regional data consortium, to publish findings, and create educational materials for dissemination across the region.

- The Board is composed of individuals with a wide scope of experience, and we quickly found that there are common themes running through our current interests and areas that we feel will be important for Medication Management and Safety in the near future:

A Broader Definition of Medication Error:

The group adopted a working position that the most useful definition of medication error for our examination of end-to-end medication management and safety in the region is that of the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (www.nccmerp.org) which defines medication error as, ‘any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer… including prescribing, order communication, product labelling, packaging, and nomenclature, compounding, dispensing, distribution, administration, education, monitoring, and use’.

This definition is felt to be particularly useful as it has a taxonomy of error type, and categorisation of error cause.

The group reached a consensus that medication errors can occur throughout the whole of the process, from supply issues requiring substitution medications through to administration, and that any change in process allows an opportunity for deviation from administration practice and for medication error.

Deep integration of medication management processes with the Electronic Health Record (EHR) and the use of ‘exceptions’ or medication ‘enrolment’ first on the EHR core system (to act as the true reference for the change) and only then on the Computerised Prescriber Order Entry (CPOE) system’s formulary, and the formularies of Automated Dispensing Cabinets (ADC) and Smart Pumps is suggested by the group as the optimum option for managing substitutions and dose unit changes.

‘To Err is Human’ and Bridging the Gap:

Medication Management, despite technology application, remains a human process and we recognise that unsanctioned workarounds to established processes from anyone in the medication chain can very quickly become a potentially dangerous and unauthorised ‘standard practice’.

With this in mind, ‘transparency’, and how systems we create for Medication Safety and Management can both uncover and catch discrepancies between what is prescribed, dispensed and administered, was reviewed. Key features of a transparent system are:

- Verification of all prescription orders in the pharmacy.

- Control and tracking of high-value and high-risk medications via the EHR.

- For opiates it is suggested that system-wide order sets, and EHR protocols that use morphine-equivalency measures during prescription and reassessment of pharmacotherapy regimens are of value, with an integrated ADC’s single unit-dose dispensing facility, and low-dose single administration units (e.g Morphine 5mg prefilled syringe) acting as controls on administration

- Employment of the technology of GTIN/GS1 barcoding in tracking medication usage allows serial, batch, and lot numbers to be identified throughout the medication chain, down to administration to the patient. Integration of medication inventory systems into the EHR also allows accurate tracking of medications entering the organisation, and whilst not all medications sourced in the Middle East are GTIN/GS1, it is our experience that over 70% and up to 100% of the medications entering our facilities are. The potential impact this has for reducing expired medication waste in a facility is very large.

Engaging the Patient:

Returning to the theme that Medication Safety and Management is ‘human’ the Board recommends reaching out to patients via personal health records held in part by the patient, such as Malaffi (‘my file’) in Abu Dhabi’s Health Authority, and through other patient applications to improve reporting of issues by patients and to help our understanding of Adverse Drug Events in outpatients and outside of the hospital. Patient engagement is a key aspect of medication safety and has the potential for making a significant contribution to improving compliance with medication regimens and with medication reconciliation processes. In terms of patient compliance and satisfaction, we suggest the following as useful initial strategies drawn on the experience in our facilities:

- Reducing times between refills by reducing the dispensed amounts at each visit.

- Texts to remind patients for medication self-administration, appointments, and tests.

- Delivery of medications to homes.

The Engine Room of the Hospital:

Turning to IV Medication Safety and Management, we first reviewed compounding, and the pressure faced by pharmacies supplying up to 600 batches of IV medications daily in larger facilities.

Batching is commonly undertaken by technicians supervised by a cleanroom pharmacist, and the technician follows a ‘recipe’ from the EHR. The pharmacist checks the ingredients, and the technicians proceed to create a batch of doses with these ingredients. We feel the weakness here is that the technicians may not achieve the correct dose in each batch, with under/overdosing possibly occurring in each individual dose made.

It was a common experience among board members that batching forces multi-tasking pharmacists into a position of witnessing only complex steps and accepting that simple steps will not be witnessed for lack of time. In terms of cost/waste, any error made in batch preparation, even if found in only one prepared medication, requires that the entire batch be destroyed and started over.

We recognise that physical and mental fatigue among pharmacy technicians is a very real reason for medication error, again medication management is a human process. With this in mind it is vital that technology we deploy in the cleanroom, as in all medication safety systems right down to the bedside, must help the user but also STOP the user from continuing in a dangerous manner. Lack of knowledge is not commonly the cause of medication error, most errors are ‘performance slips.’ Technology generated Hard Stops are therefore vital.

IV Medication Administration Safety:

Moving out of the central pharmacy, we believe it is possible for senior pharmacists to continue to influence medication safety across the facility through technology and through human systems such as planning and therapeutics committees, with specialist groups for specific areas such as neonatology, oncology, pediatrics, and elderly care. Engaging with physicians, nursing staff, and clinical pharmacists and the sharing of results and achievements in medication safety across the organisation through these inter-disciplinary alliances is vital.

In terms of IV medication safety we strongly advocate a cascade of medication safety from the core EHR IV formulary acting again as the central reference. This requires rapid update and alignment with the central formulary of smart pump medication libraries, and the use of dosing Hard Limits that cannot be overridden, rather than Soft Limits by the end user for IV medication dosing.

We suggest that the use of Soft Limits should be restricted, to avoid nuisance alarms, as a reduction in extra alarms that are not of value to the end-user increases compliance across the organisation in our experience.

The cascade from the core EHR formulary to the patient’s bedside should also include IV medication labelling, with appropriate warnings for high-risk medications that match the same medication’s alerts on the ADC, with the clinical advisory on the IV smart pump, and on the patient’s EHR medication administration record.

Even in a ‘joined-up’ and well-integrated IV medication safety system it is important to recognise that new errors can be introduced into the medication safeguarding chain by these same systems; an example being the non-separation of active treatment in some EHR medication records from medication regimens that have been discontinued. It is therefore vital, at all times, to:

- Consistently ascertain if the system is functioning correctly and responding rapidly to changes in treatment and medication supply needs in the facility.

- Review how partial, or unfinished integration may be causing more problems than having stand-alone systems with other safety gates.

- It is also important to look at how other systemic processes operating within the facility may give us information on how well our medication safety and management system is functioning.

- Financial and charge systems operating within EHRs can, for example, act as an effective double-check on administration and as a discrepancy check – as the charges in the patient record would be less than expected if the drug has been dispensed but not administered.

Looking to the Future:

Looking forward to areas that we feel will be important for Medication Management and Safety in the near future, we feel that Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems that constantly check the system’s effectiveness against parallel data may be a ‘real-time’ solution for discovering gaps in medication safety systems, and that these should include review at any point in time of antimicrobial usage, prescribing trends, availability within the hospital group and region of medications, and the total stock available within the facility.